Getting Down to Business: FAA UAS Symposium Promotes Existing Regulatory Frameworks and DAC Meeting Focuses on Remote ID, Counter-UAS

Last week, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and Association for Unmanned Vehicle Systems International (AUVSI) held the fourth annual UAS Symposium in Baltimore. Following that three-day conference, on Thursday the Drone Advisory Committee (DAC)—the federal advisory committee that advises the FAA on UAS regulatory and policy issues—held its first meeting following the appointment of 12 new members last month. The Symposium focused heavily on how industry can use existing FAA regulatory structures to break new ground, while continuing to emphasize the FAA’s commitment to aviation safety. The DAC Meeting resulted in three new task groups geared at solving issues that continue to delay the growth of the industry (Remote ID, Counter UAS, and Part 107 Waiver Process)—although in some ways, the meeting raised more questions than it answered about the future of UAS regulation.

Couldn’t make it out to Baltimore or Crystal City? Here’s what you missed.

The Symposium

A few themes pervaded this year’s Symposium: (1) a focus on creative solutions for advancing the UAS industry during the pendency of key FAA rulemakings; (2) a recognition that the drone industry is becoming more sophisticated, with an eye toward the future integrated aviation landscape; and (3) an expected, continued focus on aviation safety and security.

First, a bit of background. Last year, the Symposium theme was “Open for Business.” Going into that Symposium, the FAA recognized both that its Part 107 rules enabling commercial UAS operations contain significant restrictions (e.g., they prohibit flights over people, beyond visual line of sight (BVLOS), or at night), and that new rulemakings to allow expanded commercial drone operations would continue to be delayed. (Indeed, the Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) on flights over people initially slated for release in January 2017 was still delayed as of the 2018 Symposium due to concerns of security stakeholders about the need for rules requiring capabilities that enable the remote identification of UAS in flight (Remote ID)—something which legally couldn’t happen as long as the statutory exemption for drone hobbyists from the 2012 FAA Modernization and Reform Act (FMRA) remained in effect, which it did at the time of the 2018 Symposium.) Thus, the FAA chose the “Open for Business” message to convey that although broad enabling regulations for expanded operations were still in the future, the FAA was interested in—and able to—move the industry forward by other means on case by case bases. The crux of this openness at the 2018 Symposium was the ability to grant waivers from Part 107 and exemptions for larger aircraft or non-waivable Part 107 provisions under Section 333 of the FMRA. The FAA also emphasized the extent to which the Integration Pilot Program (IPP)—then in its nascent stages— could provide the FAA with data and experience that could continue to move the industry forward.

Fast forward to this year, and the 2019 Symposium emphasized a similar but distinct theme: Getting Down to Business. This seems to be a reflection that several significant legislative, regulatory, policy, and industry-driven developments in the past year have turned the concept of routine expanded UAS operations from a vision into (more of) a reality, though still not through broad enabling regulations. Here are some of the main developments:

-

The 2018 FAA Reauthorization Act (Reauth) reformed the hobbyist loophole and included a provision expressly permitting the FAA to impose Remote ID rules on hobbyists;

-

The IPP projects are well underway across the country, and are in fact enabling a wide variety of expanded operations and providing the FAA with valuable data;

-

Google Wing obtained a Section 44807 (Reauth’s version of Section 333) exemption and air carrier certification to conduct BVLOS package delivery operations, which will happen first through the Virginia IPP;

-

A Remote ID NPRM is on the calendar, although the anticipated date keeps slipping—currently slated for September 2019;

-

The FAA released an NPRM on flights over people, although industry generally felt the proposal was too conservative and raised implementation questions; moreover, no final rules will be adopted until Remote ID rules can be adopted simultaneously; and

-

On the first day of the conference, an operator received a Part 107 waiver to enable flights over people nationwide, primarily because of the operator’s use of a parachute system manufactured by ParaZero that complies with a new ASTM standard (hear our podcast about drone parachutes and the ParaZero waiver here).

The FAA was able to leverage the current state of play throughout the Symposium programming to demonstrate the real ways in which the industry can use FAA channels to break new ground despite the lack of rulemakings. As set forth above, we noticed a few common themes: (1) creative solutions for advancing the UAS industry; (2) an eye toward long-term challenges and opportunities; and (3) as expected, continued focus on safety. A few points on each below.

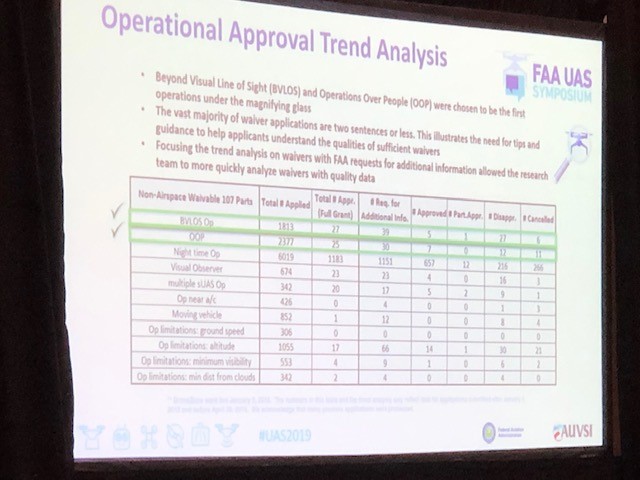

Creative solutions for advancing the UAS industry. While last year the FAA expressed it was Open for Business through exemptions, waivers, and the IPP, this year the FAA had a fuller picture of the opportunities in these avenues. Obviously, the FAA touted the Wing case, the new ParaZero waiver, and all of the ongoing work in the various IPP projects as demonstrating how operators can break new ground through these processes. There was an emphasis, in the words of an FAA moderator in a panel featuring both Wing and PrecisionHawk, on “dispel[ling] with the notion that it’s difficult to work with the FAA or to get access to the airspace.” At the same time, some of the programming demonstrated just how much work goes into these extra-regulatory approval processes, how comprehensive an operator’s safety case must be, and how infrequently relief is granted. Take for instance the chart below on the number of waivers granted versus applied for in various operational categories, or the fact that Wing had been working on its air carrier certification and exemption since 2014.

But, in addition to these now-traditional avenues for expanded UAS operations, the Symposium also focused on a number of new ideas for how to advance the industry without new regulation.

Interestingly, while drone policy has to date focused mainly on the ways that drones are different from traditional manned aircraft and need their own rules, much of the discussion this year was on how UAS operators can use existing processes first established in the manned aviation context to conduct new or expanded UAS operations. For instance, there was significant emphasis on both type certification—the process by which the FAA determines that an aircraft is airworthy—as a means to verify aircraft safety and improve the case for conducting expanded operations, as well as Part 135 for air carrier certification. The Wing case implicates both of these. (Although the Reauth Act requires the FAA to develop UAS-specific rules for certifying air carriers, the FAA certified Wing pursuant to the existing Part 135 process and exempted the inapplicable provisions). Similarly, thinking ahead to urban air mobility (UAM) applications, there was discussion of leveraging the FAA’s Part 23 airworthiness standards for commuter airplanes. In addition to these purely regulatory processes, the FAA used the Symposium as a platform to announce a new contracting opportunity for partnership with commercial companies willing to match a $6 million FAA commitment to conduct additional UAS integration work at the seven UAS test sites across the country—another way to expand industry operations without new regulations.

Consideration of long-term challenges and opportunities. The focus on opportunity for expansion through traditional aviation frameworks demonstrates the increasing sophistication of the UAS industry to tackle these more complex regulatory processes. As the Director of the Mid-Atlantic Aviation Partnership (home of a UAS test site and epicenter of the Virginia IPP) Mark Blanks put it, “UAS are growing up.” As such, this year’s Symposium reflected an expectation that the more advanced use cases such as package delivery and UAM will be realized and become routine, and emphasized the need to think about shaping policy decisions now that will enable sharing of the airspace between manned and unmanned operations in the future. A common refrain was “integration, not segregation,” which refers back to the FAA’s mandate from the 2012 FMRA to integrate UAS into the national airspace system. As such, there was considerable focus on the policy, infrastructure, and regulatory changes needed to enable use cases such as UAM and high-altitude UAS operations, as well as emphasis on the success of initiatives such as Low Altitude Authorization and Notification Capability (LAANC), an FAA-industry collaboration that enables operators to request real-time access to airspace near airports.

Expected, continued focus on safety and security. FAA representatives seemed pleased to emphasize that drone operations are increasing in frequency and complexity without compromising the safety of the national airspace. As UAS Integration Office head Jay Merkle said in his closing remarks, “everything you heard today is about safety.” And the Unmanned Aircraft Safety Team (UAST), a(nother) public-private partnership, announced a new Unmanned Aircraft Safety Reporting System to collect data about UAS operational and technical failures.

This focus on safety is consistent with the FAA’s mission as the agency tasked with maintaining aviation and airspace safety, is thoroughly consistent with how the agency has approached UAS regulation to date, and is perhaps more important than ever given that, with a few high-profile incidents, we’ve entered the age of the drone as the new UFO. Indeed, the recent airport disruptions by alleged drone sightings brought aviation safety and security into the same conversations at the UAS Symposium. It is clear that the federal government continues to grapple with how to address UAS security issues, how to exercise the authority granted to certain federal agencies (the Department of Energy, the Department of Defense, and—through Reauth—the Department of Homeland Security and Department of Justice) to deploy counter-UAS systems, and how to ensure that these systems do not interfere with airport operations. The FAA was also careful to distinguish between drone mitigation systems and drone detection systems, the latter of which can be used by more entities than the four agencies with C-UAS authority. However, drone detection systems carry their own legal ambiguities—as one panelist noted, anyone interested in purchasing a drone detection system should consult with his her or her lawyer to ensure they don’t violate any surveillance laws.

The DAC Meeting

The day after the Symposium concluded, the DAC convened for an all-day meeting. The advisory committee welcomes 12 new members and a new chair – PrecisionHawk CEO Michael Chasen. Chasen was enthusiastic about UAS growth prospects in the near-term and emphasized the value that the DAC could bring to realizing that growth through its advisory role to the FAA. He identified five priorities for the committee under his leadership: (1) Remote ID; (2) BVLOS; (3) Counter-UAS; (4) the Part 107 waiver process; and (5) public-private partnerships. The taskings touched on all of these, though some more than others. There will be three new task groups:

-

Remote ID. The FAA wants the DAC to study existing CTA, ASTM, and SAE standards relating to Remote ID and provide recommendations within 90 days that will outline a process and framework for driving voluntary industry compliance with Remote ID. Steve Ucci of the Rhode Island State Assembly will lead this task group. The FAA’s vision appears to be that, while the Remote ID regulatory process continues to be delayed (slides and remarks at the DAC suggested the FAA is anticipating a timeline of 24 months to adopt final Remote ID rules), it can leverage industry expertise and cooperation to encourage development of Remote ID standards and have industry put them into practice without waiting for a mandate. Widespread voluntary adoption will also make it easier to justify the final standards or rules the agency eventually adopts, and/or to pacify the long-held concerns of the security stakeholders. Notably, however, none of these security stakeholders (e.g., Department of Defense, Department of Homeland Security) sit on the DAC, making it difficult to know whether the Committee’s efforts will move the ball forward on Remote ID. In any event, it will be interesting to see what incentives the committee can identify to encourage voluntary adoption of Remote ID—one idea floated was expanded access to national parks for people who agree to use Remote ID.

-

Counter-UAS. The DAC will develop recommendations on existing and emerging technical solutions that can address UAS security concerns. Jaz Banga of Airspace Systems will lead this group. This tasking discussion was far and away the most contentious of the day. DAC members expressed confusion about the task and whether it was actionable, and raised a broader concern that they perhaps weren’t being asked the right question. For instance, several industry members expressed doubt that technological capabilities being developed by industry could mitigate the ability of criminal actors to commit bad acts with UAS, and suggested that in focusing on UAS capabilities the FAA may be conflating safety with security. The discussion also veered into a more holistic view of the UAS security landscape, with members suggesting that it might be more productive for the DAC to study the proper roles and responsibilities at the state, federal, and local level to conduct counter-UAS measures and enforce relevant laws, or how to assess the proper risk tolerance for UAS security threats. The FAA seemed steadfast on keeping the DAC focused on how, under existing law using existing authorities, security concerns could be alleviated using existing or near-term industry technologies, although the FAA’s Angela Stubblefield did note that the FAA does not expect industry to provide recommendations to deter criminal acts, but rather prevent clueless and careless operators from doing any harm. It will be interesting to see how this unfolds given the friction at the meeting.

-

Part 107 Waiver Process. This working group will focus on how to improve the Part 107 waiver process, including better understanding the workflows at the FAA as well as learning from the experiences of waiver applicants. Brian Wynne of AUVSI will lead this task group. It was pointed out in discussion that a potential shortcoming of the DAC is that its industry membership is composed of the big players; as such, there’s no direct representation of small- or medium-sized operators (although, as the world’s largest industry association dedicated to unmanned systems, AUVSI represents thousands of smaller operators). There will likely be significant opportunity for these smaller operators to work with the DAC and shed light on the waiver experience from their perspective.

BVLOS and public-private partnerships were also discussed as standalone categories, but neither will result in a task group at this time. A task group on BVLOS may be set up at the next meeting.

A couple other items to note: First, in keeping with the perennial focus on safety, the FAA is planning a nationwide Drone Safety Awareness Week for November. The DAC membership seemed receptive to this concept and had several ideas on how to make it successful. Second, the FAA gave an update on its regulatory efforts, but notably absent were the rulemaking on UAS-specific air carrier operations mandated by the Reauthorization Act as well as the rulemaking to implement Section 2209, the provision of the 2016 FAA extension bill that requires the FAA to create a process to designate critical infrastructure over which drone flights are limited or prohibited (after the deadlines from the 2016 legislation came and went, the 2018 Reauth Act imposed a new deadline of March 2019 for an NPRM, which, like the first, came and went).

Update 9/13/19: Materials from the June 6 DAC Meeting are available here: https://www.faa.gov/uas/programs_partnerships/drone_advisory_committee/media/eBook_6_2019_DAC_Meeting.pdf.